Connecting national park rangers in the world’s most austere locations

With temperatures regularly reaching 122 Fahrenheit, deadly animals roaming the terrain, and the constant threat from armed poachers, the park rangers in southern Africa’s national parks confront hazardous and challenging conditions. They face these dangers to protect something priceless – some of the world’s most endangered and vulnerable species.

African park rangers work in some of the world’s most austere and remote locations. Operating off-grid and away from major urban centers also means that rangers need access to essential communications and situational awareness capabilities.

To try and help overcome their communication challenges and make their jobs safer, goTenna ventured to two of the largest national parks in southern Africa to conduct mobile mesh field tests. The Last Mile recently sat down with Michael Gibbs, Associate Director of CX at goTenna, to discuss the importance of these parks, the challenges these park rangers face, and what the field tests revealed.

The Last Mile (TLM): goTenna conducted a two-phase field test in South Africa last month. Can you tell our readers the significance of these national parks and the goal of the Peace Parks Foundation?

Michael Gibbs: These parks are two wildlife sanctuaries in Africa that aim to protect wildlife from poachers. One is about the size of the state of New Jersey, sitting at approximately twenty thousand square miles, and holds sixty percent of the world’s existing rhino population.

To put things into perspective, a single rhino horn on the black market sells for twenty-five thousand dollars per kilogram—making poaching a real problem in these areas. Poachers have to kill the rhinos in order to dehorn them.

“These areas are in very remote environments with unique communications challenges. Without access to reliable off-grid communications technology, this type of austere environment could affect how wildlife rangers track or communicate with each other.” — Michael Gibbs

The Peace Parks Foundation is a group of people whose core purpose is to protect these animals to ensure they thrive and can be observed by visitors today and in the future. These parks have the same objective. However, they reside in different regions, resulting in disparate policies and rules against poaching. The Peace Parks Foundation works with countries in the region to find effective methods of dealing with the unique issues which arise from establishing and maintaining these large conservation parks.

TLM: What was the primary goal of these field tests? What was goTenna trying to accomplish?

Michael Gibbs: We conducted these field tests with our partner, Tough Stump Technologies. Our purpose for these tests was to provide a communications infrastructure that could enable communications and situational awareness capabilities for rangers in both national parks.

These areas are in very remote environments with unique communications challenges. Without access to reliable off-grid communications technology, this type of austere environment could affect how wildlife rangers track or communicate with each other.

TLM: I understand that some technologies are already in place in these national parks to help with situational awareness. What are they using? Does it meet all of their requirements?

Michael Gibbs: Park rangers are already leveraging the ATOS tag technologies from Tough Stump. ATOS allows individuals in the field to track essential assets, personnel, and equipment.

“Establishing communications for rangers is critical for both mission success and safety.” –Michael Gibbs

Combining the functionality of the existing ATOS tags with goTenna mobile mesh networking solutions creates an avenue to push data back to decision-makers. The goTenna mobile mesh networking solutions also deliver communications capabilities critical for collaborative operations in the field.

TLM: What were the results of the first field test? What challenges were faced, and were there any significant findings?

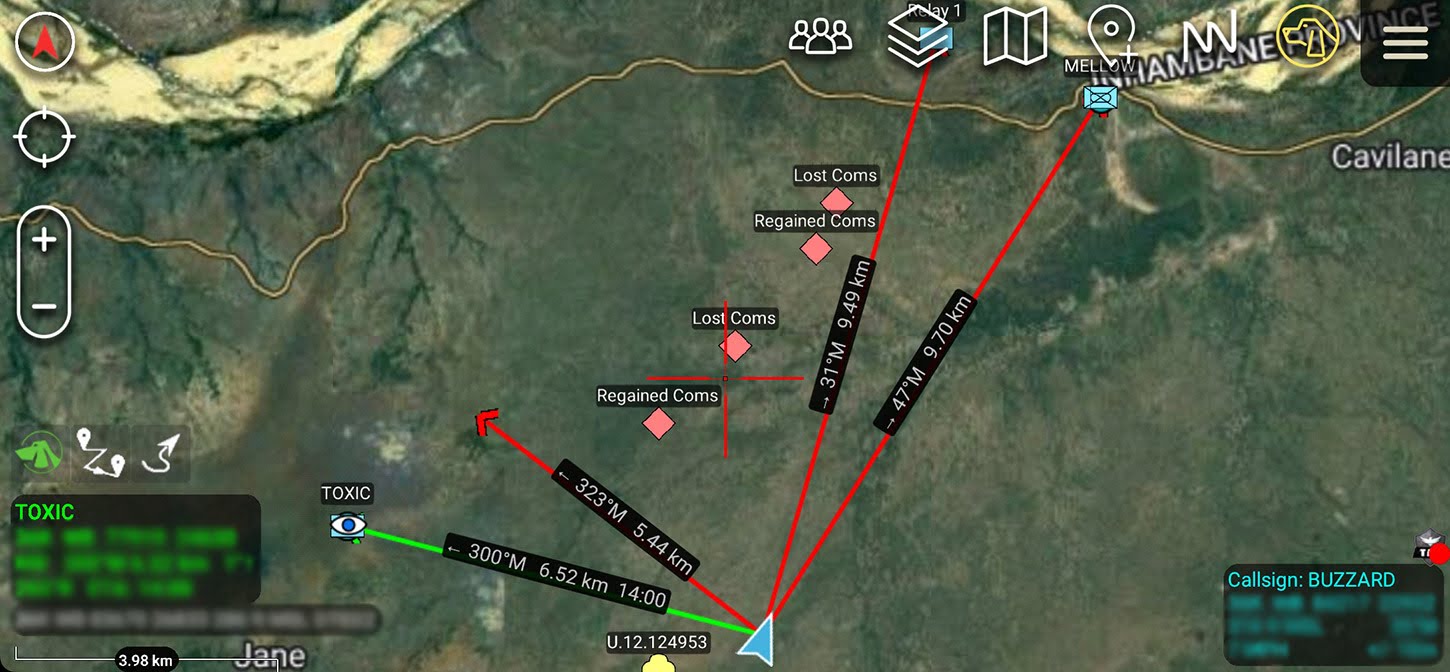

Michael Gibbs: For the first field test, we traveled to Mozambique to demonstrate local command and control for the park rangers and establish a backhaul connection from the central camp throughout the rest of the park.

Since ATOS tags were already being used within the park, establishing a backhaul connection for these ATOS tags was the priority. The field test demonstrated that the ATOS tags could transmit data across a mobile mesh network.

The off-grid nature of this region benefited the goTenna mobile mesh network. The lack of people, infrastructure, and other technologies drastically reduced the electronic interference the goTenna Pro X2 devices experienced. Nothing interfered with the mobile mesh connection, so establishing a connection was relatively easy.

The real challenge involved geography, topography, and line-of-site. Thankfully, we identified three towers within the park, allowing us to place goTenna Pro X2 devices at a higher elevation. The mobile mesh network could cover a substantial distance with relays strategically placed at the top of the towers.

The goTenna Pro X2 devices consistently performed well with no challenges, and the longest distance achieved was 19.86 miles.

TLM: The second field test occurred in South Africa. How was this field test different from the Mozambique test? What were the results of the test?

Michael Gibbs: Working in the South African park was an entirely different scenario. As previously mentioned, this park is enormous and located in a more developed area than Mozambique.

The South African park is more of a tourist attraction, which results in more interaction with civilians and the public. The terrain is also very flat, with some significant high areas. These high-altitude spots can elevate mobile mesh radios and improve line-of-sight communications.

Our goal was to cover the southern area of the national park. Our main objective was to establish a backhaul network to enable communications and situational awareness between the field and operations center rangers. We were also attempting to establish contact between park rangers on the ground.

Establishing communications for rangers is critical for both mission success and safety. Not only do these rangers face the threat of poachers, but they are also working in a “live zoo” with wild animals that can be hostile if they feel threatened. Being able to communicate and request assistance is not only essential for collaboration but also for getting help or backup.

As part of the field test in South Africa, we established network connectivity over a substantial distance of 58 kilometers (approximately 36 miles). During the test, rangers on the ground in different locations communicated quickly throughout the park and with the operations center — making both field tests a massive success.

No Comment