Tech Spotlight Series: Veterans improve disaster readiness and make a better “bad day” for communities

Fix it in post! That’s often heard in the film industry. But industry professionals know that any work done after the fact is far more expensive than good planning and preparedness. When it comes to disaster readiness, professionals likely know the same is true. Well-informed training, solid planning with local resources, and built-in resiliency all help communities survive and recover more quickly and more sustainably.

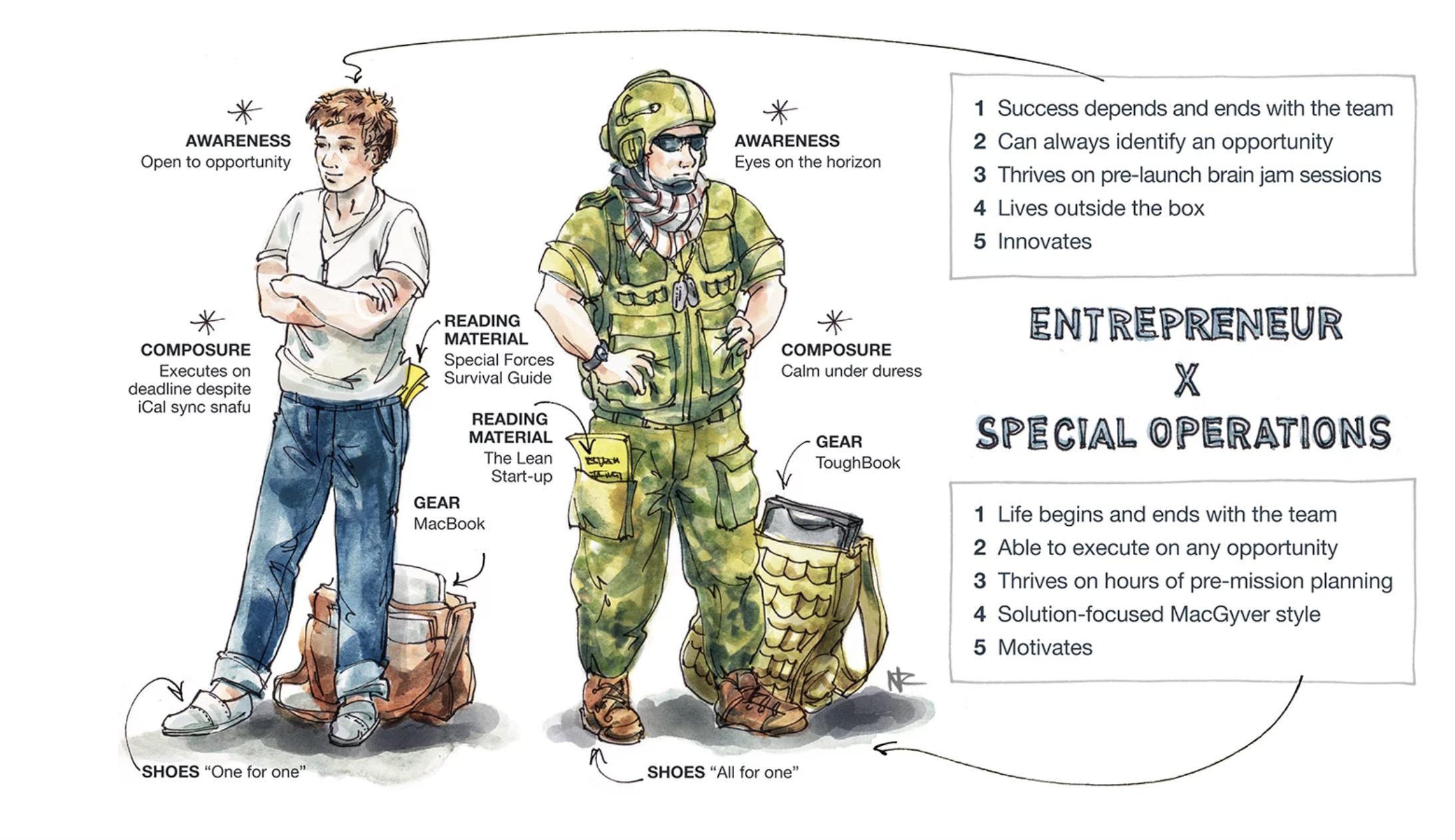

In our communities, some of the people best trained and prepared for disaster response are our military veterans, entrepreneurs, and small business owners – although they might not realize it. The ability to make rapid decisions accounting for available resources is what veterans and entrepreneurs carry with them inherently. Recognizing this value in the private sector, and in disaster training and response, can yield a better “bad day” for communities.

Tactivate, a disaster readiness, response, and training organization with more than a decade of experience responding to large disasters, is on a mission to connect trained military veterans, entrepreneurs, and first responders to their communities by proactively training communities and businesses on how to prepare and respond to disasters. Resilience is at the heart of Tactivate’s methodology.

The Last Mile sat down with Jesse Levin, founder of Tactivate, to discuss the current state of disaster readiness in the U.S. and learn more about how Tactivate is working to increase readiness in communities.

Here is what Jesse had to say:

The Last Mile: Can you tell our readers a bit about Tactivate? What is the organization’s mission? How did it get its start?

The Last Mile: Can you tell our readers a bit about Tactivate? What is the organization’s mission? How did it get its start?

Jesse Levin: I have a background in culture mediation and austere environment logistics. I ran a firm in Panama for five years, doing a lot of work in remote and more contested areas.

I launched Tactivate directly after coming back to the U.S. from Panama when I spent over six months doing disaster relief related work following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

We found that there was a huge disconnect between the military veteran and business community. We recognized the capability and capacity of veterans and how valuable it would be in business. So, we launched Tactivate to do two things:

To launch ventures hand in hand with Special Operations Forces (SOF) veterans to employ their expertise and to provide real-time, real-world business experience post service. There’s a misconception of who these folks are. And we found that by creating environments through these businesses whether they were bars, or climbing gyms, or co-working spaces individuals in the private sector were able to see the value that these veterans brought to the community while affording the veterans with a unique way to build experience and to grow networks.

With the revenue generated from these activities, we sponsor volunteer international disaster readiness, response, and economic stability efforts. We send small teams focused on last-mile organizational and human resource terrain mapping to help with the initial disaster response needs, with the main focus during the acute response phase of training and outfitting the impacted community to future proof them against future impacts. By assessing the systemic breakdowns, rapidly cultivating awareness for, and relationships with local actors we are able to direct resources to them, decreasing dependence on external actors and empowering economic stability to commence as early as possible. In this way, we hope to decrease the detrimental impact of well-intentioned but sometimes misplaced “aid.”

The Last Mile: With over 10 years of experience in disaster response organizations, you personally had “boots on the ground” in the aftermath of several disasters, including the Haiti earthquake, typhoon Haiyan and Hurricane Maria. What are conditions like in these disaster environments? How does the loss of infrastructure impact first responders and community members?

Jesse Levin: They’re inherently chaotic, disorganized environments. But, at the same time disasters also bring out the best in people and communities. The level of ingenuity, creativity, and the goodwill that manifests very quickly is incredible.

Our role in the ecosystem, if you will, is a bit different than traditional aid organizations in that we go to the very last mile. We try to identify the systemic, underlying issues that might not necessarily fit the traditional checkboxes of international response or NGO organizations. We try to analyze and map local organizational and human terrain very quickly to identify unconventional local resources whether it’s the teenage hacking group or a local business person that has infrastructure still in place post-disaster. Our philosophy is to see and focus on the positive impact potential of all players within the Humanitarian Assistance Disaster Response (HADR) ecosystem from government, military, NGO to contractors, and most importantly local players and to work to connect them informally. While these groups might not conventionally collaborate or play well together, it has been our experience that providing a common operating picture and a platform to connect them, all outside the confines of traditional response constructs, leads to incredible last-mile impact.

Regarding the conditions in which we work, there’s often rubble and flooding everywhere. It might seem unpleasant for many, but for us, it’s our arena where we get to practice our trade. Just as mountaineers consider the mountains their home despite conventionally unpleasant conditions, we consider disaster zones our home. It’s where we thrive and are most comfortable operating. The crazier or more disruptive the environment is, the more we tend to latch on to the entrepreneurial spirit and comradery that manifests in these environments. We are able to operate in a more self-sustained manner which allows us to move more freely. Understanding the mechanics of disasters and the resource communities that form, we are able to leverage the incredible resources brought to bear by respective agencies or large orgs to cover a lot of ground more quickly than is convectional.

The Last Mile: Based on your experiences, what needs to change in the traditional disaster response playbook?

Jesse Levin: I think predominantly traditional disaster response is very predicated on reactionary recovery efforts with the vast majority of resources activating post occurrence. NGOs, for example, can raise a lot of money when they start showing a lot of imagery and videos of devastation, but that whole dynamic is just sort of backward. Instead of waiting for something to happen we need to shift, societally to being more prepared and to investing in proactive readiness. This requires a drastic shift in operational culture, resource ecosystems, and general public sentiment – but it’s starting to happen in a big way.

How can we simulate the same level of interest, ingenuity, and technology efforts that manifest in the immediate wake of a disaster in advance of one striking? How can we proactively train young people, individuals, families, communities and local businesses to be connected, outfitted, and organized? How can we harden them, and future-proof them so that if something happens again, there are local, existing resources that can be leveraged?

A lot of aid, as currently deployed, in some ways is detrimental to the local economic environment, recovery, and stability it’s intended to facilitate. Clearly that is not the intent, but there is a cause and effect relationship that many who are not active in the arena are not privy to seeing and experiencing firsthand. While well-intentioned, consideration is not always paid to how all of the external resources and labor that flood into impacted areas affects market dynamics and potentially further disrupt the local ecosystem of service providers and supply chains.

There is an easy and cost-effective way to change this dynamic that is both more economically advantageous than the current status quo and much more beneficial for vulnerable communities. If local gas stations, local merchants, and banks put very simple, redundant systems in place before something happened, they would become capable of providing continuity of service and serving as the critical last mile infrastructure that they should be. We want communities to be self-sustaining and resilient which inherently requires that they be proactively ready to handle disruptive times more independently and less dependent on external support. To begin to facilitate this paradigm shift from the bottom up, we have used the acute response phase to help put training and systems in place so that the next time something happens that community is better outfitted, organized, and ready to handle whatever might come their way on their own.

The Last Mile: How will these ideas translate into the courses and technology offered at Tactivate’s new training school?

Jesse Levin: We’re in the process of launching The Readiness Collective, the first emergency readiness training club, gear gallery, and outfitter of its kind. We’ve been experimenting with and developing methodologies around disaster response, economic stability, building collective community capacity, and enabling business continuity both in the private sector and in the humanitarian arena for over a decade now. Core to our efforts has been working to identify ways in which to educate people and businesses in these areas and to teach skills in a manner that might be far more approachable and accessible than current avenues. The subject matter experts, equipment providers, and instructors in the readiness and preparedness arena are out there in spades. But the majority of everyday citizens and businesses have no idea where to start, how to find these resources or even who or what they should be looking for. As a result, readiness is just not as accessible and normalized as we think it should be.

Jesse Levin: We’ve learned that it doesn’t matter whether you’re in Haiti, the Philippines, or in Connecticut. Everybody is susceptible to aging infrastructure, lack of upkeep, and a generally unprepared society. It’s not new to us, but it’s new to people who are becoming increasingly aware that they are vulnerable and cannot be dependent on the systems that they are usually dependent on even in the most developed and wealthy counties in the U.S.

When you layer COVID on top of that in all of these preparedness measures, people don’t quite realize yet how that’s going to impact police departments, EMS, and other resources. Our municipalities are going to be hurting for funding given the decreased tax base because of COVID.

Generally speaking, we don’t have a society that’s really neighborly. For the most part, it’s more of a “we” versus “they” construct. Whereas in other regions like Latin America or emerging markets in developing countries, people are more accustomed to banding together out of necessity. They are more used to having to work together in a community to get through these types of things. So, I think that’s a huge wake-up call for the U.S. population and I think it will drive us to become closer as a country and more tolerant.

The Last Mile: You recently had the opportunity to test mesh-enabled mobile apps and goTenna Pro devices. How do you think off-grid mesh networks can fit into typical disaster response activities? What role can they play?

Jesse Levin: I think communications is first and foremost the most important resource in disaster response. Without communications, how do you get accurate situational awareness? With power outages and aging cell phone infrastructure, communication networks go down more frequently then we all might care to admit. Mesh networks like goTenna’s are very easy to use and relatively effective, especially at the community level. Mobile mesh networking makes a whole lot of sense for multiple scenarios — from school security situations where they might lock down cell phones, to when a storm hits and knocks out cell service for more than a week like what just happened in parts of Connecticut with T-Mobile after Tropical storm Isaias.

Being able to communicate — having folks proactively connected with their neighbors, and even tied into the local emergency response infrastructure — is really important and can easily and cheaply be accomplished with mesh technology. Not everyone is going to have a HAM radio operators license, and tools like goTenna and Garmin InReach are really important to look at and to become familiar with. It’s not hard to accomplish this on an ad hoc basis very effectively with mobile mesh networking technology. It’s important that these measures are tied into a more complex emergency communications system. But, it’s a really valuable tool and a great start.

The Last Mile: Looking at the big picture, how will you measure the success of Tactivate? And similarly, how do you encourage your customers to define goals and success with their own disaster and emergency preparedness planning?

Jesse Levin: We think there’s an opportunity to help curate access to readiness. There’s a branding problem—preparedness has become very stigmatized and many of the experts in the field are more tactical in nature — turning many off. A new type of point of entry and access for all things readiness and resilience-related is needed. Not to recreate the wheel but to help the uninitiated navigate the process of making ready and finding the best trainers and providers in the field. Preparedness can’t be purchased. It’s a process and a practice that must be cultivated. To that end, those providing training are very segmented and siloed with people doing amazing work but remain hard to find.

Our goal is to really help the community of nonprofessionals gain access and insight into the readiness community and the goTenna’s of the world, the water purification companies, the medical training, and emergency medical equipment outfitters. Our goal is to really evangelize that.

You can keep up to date with Tactivate’s launch of The Readiness Collective here.

No Comment