Puerto Rico and the unique challenges of emergency response in island communities

It’s almost impossible to deny the fact that “100-year storms” are happening almost every disaster season. And now in the midst of an unprecedented pandemic, emergency management agencies are all too accustomed to preparing for the worst.

But emergency response isn’t the same everywhere. Emergency situations in some geographies and locations are harder to respond to than others. And we, unfortunately, got a stark reminder of that when Puerto Rico was slammed with two hurricanes in the span of just a few weeks in 2017.

Natural disasters in geographically isolated and remote locations like islands come with their own unique logistical and communications challenges that we don’t have to worry about on the mainland. Let’s take a look at why the disasters that hit island communities like Puerto Rico create so many problems — especially for communications and situational awareness.

Challenges of providing emergency assistance to island communities

Being surrounded by water poses many challenges for disaster relief and recovery efforts to Puerto Rico and other island communities in the Caribbean.

When hurricanes or earthquakes hit, they compromise much of the ground infrastructure. The ports, airports, roads, and other transportation infrastructure are often destroyed or badly damaged. Unlike a location on the mainland, there isn’t an option for military and emergency response personnel to simply get into trucks and other vehicles and drive to the scene. They have to find new roads and routes along the way as the situation continues to evolve.

The disaster response effort brings in a lot of people, all of their equipment, and a seemingly endless stream of supplies. Moving that personnel and equipment is a logistical challenge that is unlike anything recovery teams in landlocked communities have ever experienced — each person effectively requires their own piece of transport equipment.

How do we get those people and items to an island? Especially an island with few runways and only a few deep-water ports? They mostly have to travel by ship and arrive in the ports that are still operational and available. From there, they have to be dispatched to the hardest-hit areas, and that creates challenges on its own — especially when the infrastructure for cell, wifi, and satellite communications networks are also damaged or unavailable.

Playing catch up when radio and cell towers are down

It’s no secret that the communications and electrical infrastructure in Puerto Rico was antiquated at the time that Hurricane Maria struck. And with Hurricane Irma just a few weeks prior, they simply didn’t have the time to rebuild the towers that were impacted. However, a lesser-known fact is that Puerto Rico’s towers were impacted so significantly because they didn’t meet the same rigorous regulations and specifications as in the rest of the contiguous United States.

Radio and communication towers are suspended steel structures, but they can only bear so much weight. When winds exceed 120 MPH or when trees and other debris start to whip against them, they are not invincible —typically, they lean and break.

By regulation standards, the towers in Puerto Rico weren’t required to withstand as much weight and pressure as the towers as our towers in the mainland U.S. They also don’t have the same level of redundant backups in the event of damage or failure. Hurricanes Irma and Maria were powerful storms with even more powerful winds. Worse, the geography of Puerto Rico — an island with a mountain range running practically right down the middle — meant that the towers and communication infrastructure had to be placed at higher altitudes to work effectively where they would be even more exposed to the elements.

Following Hurricane Irma, the island of Puerto Rico was staring directly at a second hurricane with a compromised communications infrastructure, and very little time and ability to patch up networks. They never really got the chance to prepare. They only really got an opportunity to try and mitigate the damage. And the relief effort suffered because of it.

To the credit of government officials in Puerto Rico, they’re taking huge strides to remedy this situation and prepare their island for future natural disasters. But Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria both remain an example of why resilient and redundant networks are essential for emergency communications planning and preparedness.

How mesh networks operate without ground-based infrastructure

In order to enhance emergency communications, many island communities are now looking to mobile mesh networking solutions that don’t require ground-based infrastructure. Instead of sending data through a central tower or base station, mobile mesh networking systems transmit information from device to device using radio frequencies.

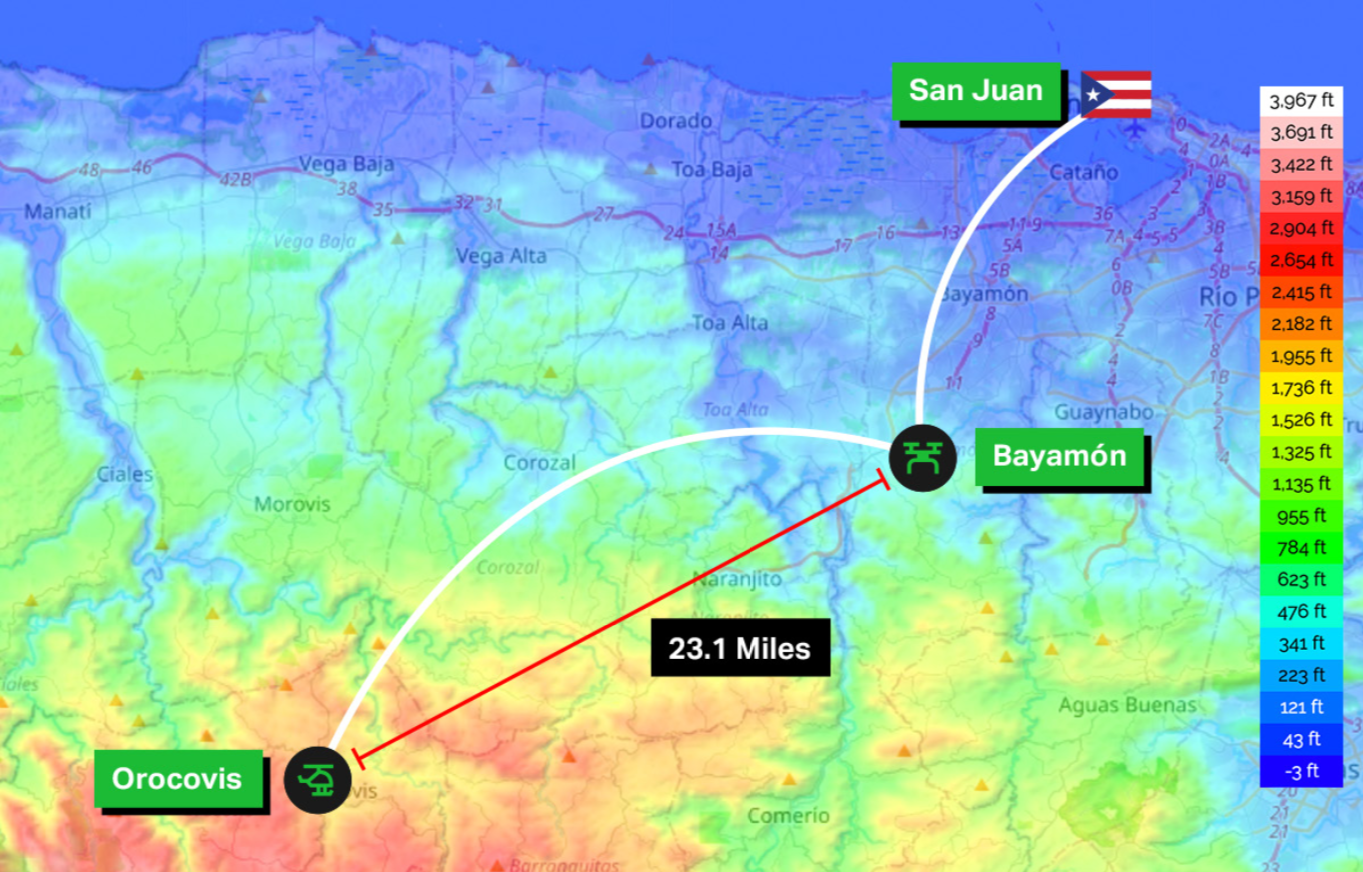

This type of network is incredibly valuable for disaster response in a geography like Puerto Rico. Equipped with a mesh networking radio device, each responder — or vehicle — can effectively become a single “node” in an ad hoc, mobile network that scales as the situation evolves. In a recent test, several technology partners in Puerto Rico (including my team at goTenna) proved how disaster teams could extend mesh network range across the length of the island with the use of aerial relays on existing drones and helicopters already deployed in the response.

Compare this to other types of communications networks and infrastructure, which require large pieces of expensive equipment to be installed. The ability to bring the network with you, with the equipment already in hand, cannot be understated. Another goTenna partner, the Humanitarian Aid and Rescue Project, actively deployed our professional mesh networking radio devices in the response to Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas — they were able to share texts and map locations post-landfall when everything else had gone dark, and it was the difference between life and death.

When responding to a disaster on an island, emergency management agencies are often forced to navigate a logistically difficult response without communications of any kind. Mobile mesh networking technology is built for unique demands of island communities like Puerto Rico — it doesn’t strain or rely on existing communications infrastructure, and it creates a reliable, off-grid network that can be deployed immediately.

No Comment